Christian Boltanski, Padre Mariano, 1994

Rebecca DeRoo

Assistant Professor, Department of Art History & Archaeology, Washington University in St. Louis

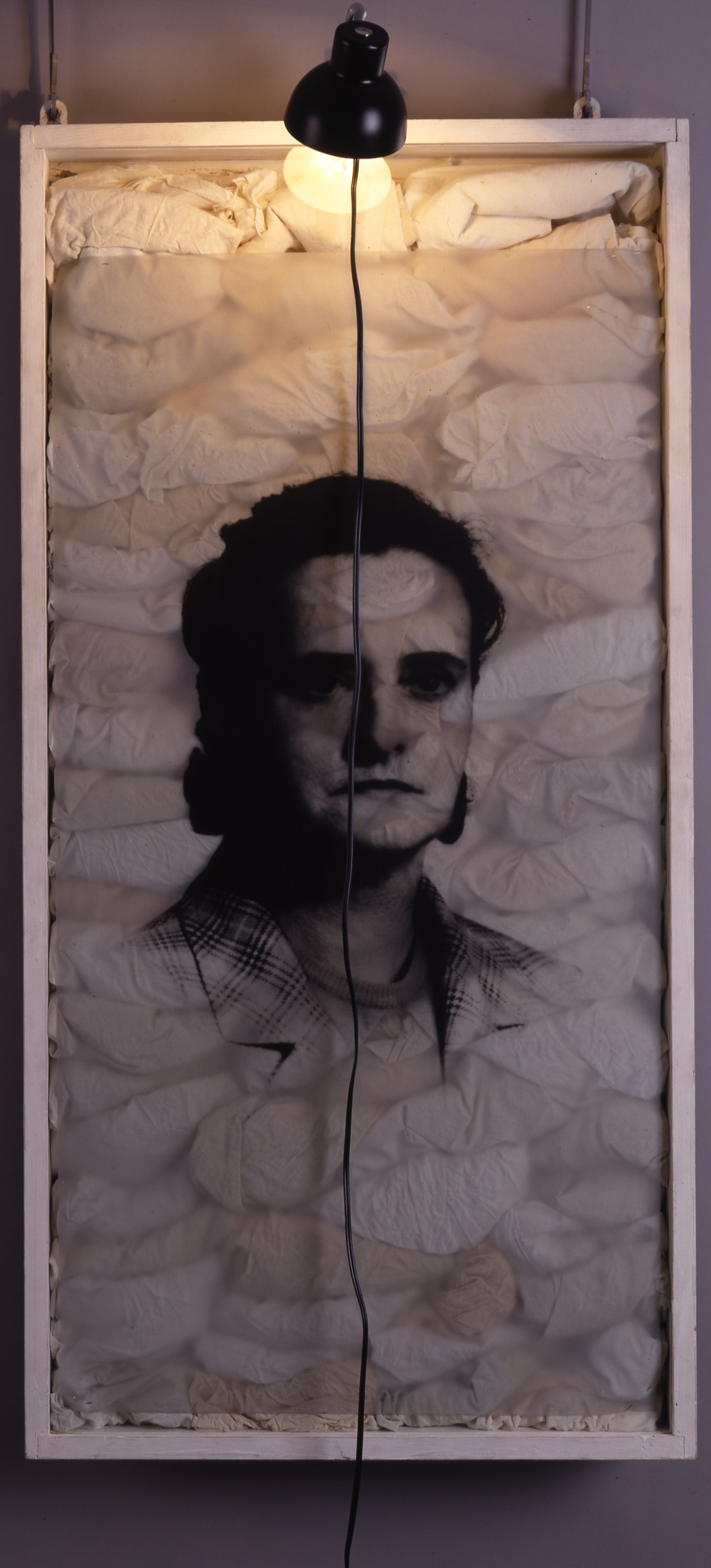

In Padre Mariano (1994) Christian Boltanski makes extraordinary use of ordinary materials, employing an anonymous photograph, display case, linen cloth, and electric lamp to create intense emotional effects and an almost religious aura. The work features an enlarged, black-and-white photograph of a woman, which is mounted on transparent Plexiglas, through which linen cloth is visible. Boltanski found this photograph, which was originally sent to Padre Mariano, one of Italy’s first television evangelists, at an Italian flea market.1 In Padre Mariano, the enlarged photograph suggests the life and memory of an individual. Yet we do not know the name of the person, the occasion for which the picture was taken, or the particular reasons it was sent to Padre Mariano. The wrinkled linen cloths behind the picture show traces of use, but the fact that they are sealed and protected within the case, preserved as almost sacred remains of the past, prevents us from gleaning more information about their specific histories. Many critics and curators have described Boltanski’s artwork as representations of memories and preservations of the past.2 Yet Padre Mariano, like much of Boltanski’s evolving work, seems to evoke memories of an individual while simultaneously questioning the possibility of preserving and communicating them to a broader audience.3

In the mid-1990s, when Boltanski created Padre Mariano, he frequently explored the idea of relics in his work, accentuating their emotional effects and religious associations.4 For instance, Boltanski’s 1996 Reliquaire, Les Vêtements (Reliquary, The Clothing) evokes the form and function of early reliquaries: elaborately decorated containers used from the fourth century through the Middle Ages to preserve and display the remains of martyred saints or objects associated with them, such as cloth. Boltanski’s 1996 Reliquaire uses simpler, contemporary materials: it is essentially a crude wooden and metal box with a screen across the front. Semitransparent photographs of anonymous children mounted on the screen give them an almost “dematerialized” presence. A florescent light inside the box creates a halo-like glow above the children’s heads, as if it were a spiritual light emanating from the contents of the Reliquaire, imbuing the images with a saintly effect. The lower portion of the reliquary contains clothes that appear to have belonged to the children. Understood within the religious context of reliquaries, these simple objects and images suggest sacred remnants from the lives of those depicted.

Padre Mariano similarly draws on the idea of personal remnants infused with a religious aura. We do not know this woman, yet Boltanski creates a strong sense of pathos with her anonymous photograph. A personal photograph is typically the means for us to recognize or remember an individual who is close to us; viewing this anonymous picture, in contrast, we feel the absence of personal ties and memories surrounding the image. The fact that Boltanski used a photograph found at a flea market—no longer in the hands of Padre Mariano—further suggests that the depicted subject has been forgotten.

The linens inside the case evoke altar cloths, sheets from hospital beds, and burial shrouds. Yet we cannot open the box to inspect the sheets, frustrating our desire to obtain additional information. As in his Reliquaire, Les Vêtements, the case preserves seemingly sacred materials from the past; but it also raises the question of why they should be preserved if the stories associated with the objects and the memories of the individual are gone. The lamp illuminates the figure’s face, as if indicating her importance, and also appears to create a halo above her head. But rather than a light emanating from inside the box (as if radiating from the sacred nature of the material), here it is projected artificially from the lamp outside, like a spotlight. Furthermore, the electrical cord dangles unceremoniously in front of the subject’s face, prompting us to question the work’s seemingly reverent, memorial function.

Padre Mariano, like most of Boltanski’s work, creates a powerful evocation of an individual’s past, but also suggests the limits of trying to preserve it. His work encourages our identification with familiar materials, yet confronts us with their opacity, continually challenging us to rethink the intersections of the individual and collective past, and the extent to which personal lives and memories can be shared.

- 1 As described by Ariella Giulivi, “Christian Boltanski,” http://vegetalignoti.supereva.it/paine/ve2.html (accessed April 19, 2000; site now discontinued).

- 2 See, for example, Lynn Gumpert and Mary Jane Jacob, Christian Boltanski: Lessons of Darkness, exh. cat. (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1988), and Andreas Franzke, Christian Boltanski: Reconstitution, trans. Laurent Dispot (Paris: Chêne, 1978).

- 3 I explore this further in my book The Museum Establishment and Contemporary Art: The Politics of Artistic Display in France after 1968 (New York: Cambridge, 2006).

- 4 For more information on Boltanski’s work from this period, see Danilo Eccher, Christian Boltanski (Milan: Charta, 1997).