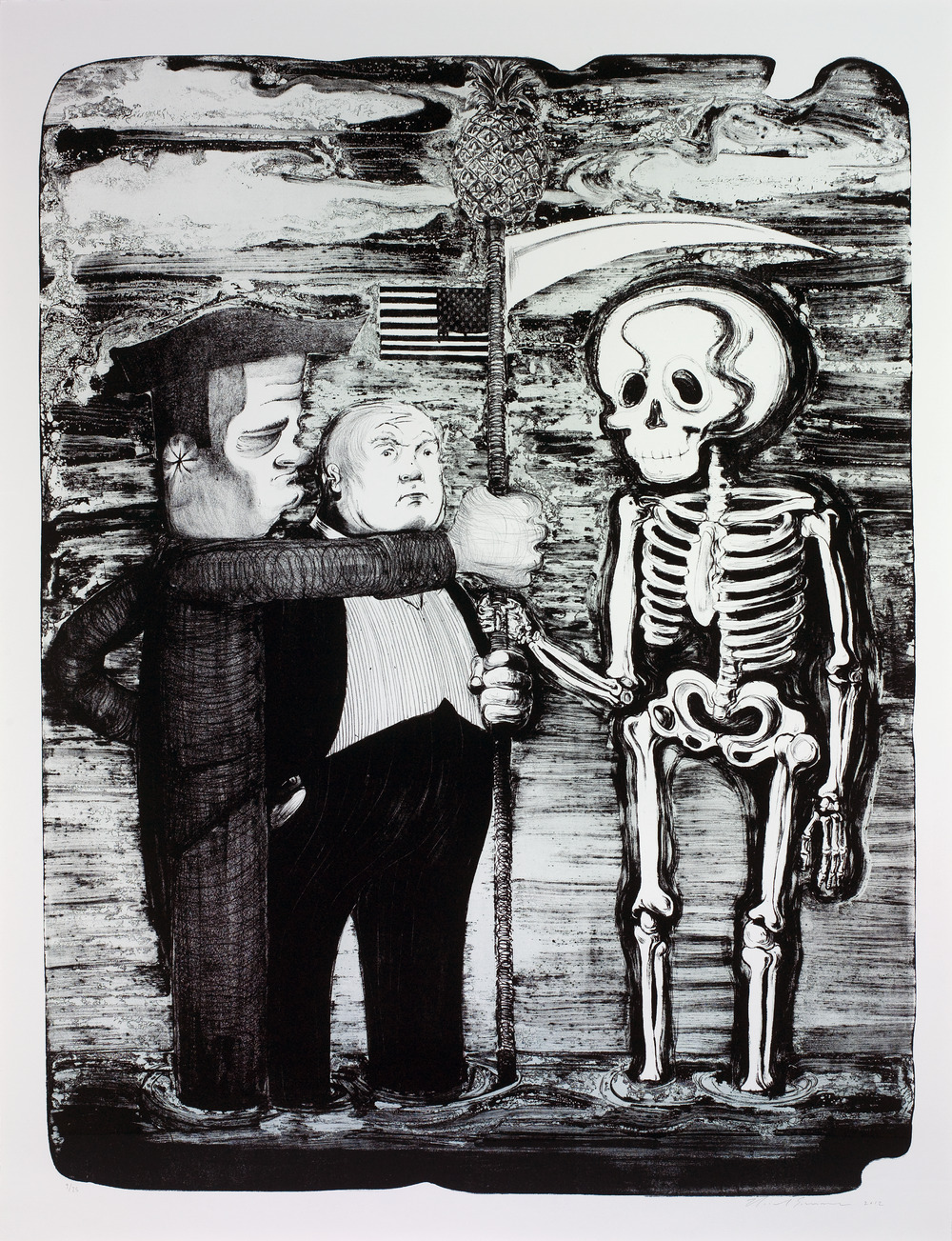

Nicole Eisenman, Tea Party, 2012

Kelly Shindler

Associate Curator, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis

Since the early 1990s the artist Nicole Eisenman has created paintings and drawings of flagrantly sexual gender-neutral lovers, all-female separatist enclaves, and more recently, beer gardens, dinner parties, and poetry readings that express an incisive, humorous, and occasionally melancholic vision of a large, inclusive spectrum of humanity. In 2011, in the wake of several major life changes, the artist locked away her paints and embarked on an exclusive foray into printmaking that would last the better part of two years. Known for her figurative works that reference a variety of art historical styles and techniques to engage contemporary issues—among them interpersonal (specifically lesbian) relationships, identity, and her own self-reflexive musings on being an artist—Eisenman turned to printmaking for its singular ability to depict an array of sociocultural conditions in a relatively fluid and often urgent manner. She made scores of monotypes, woodcuts, etchings, and lithographs during this time. The inherent properties of each printing method are reflected in the final works: her monotypes evoke a playful experimentation that corresponds to the swift manner in which they were made; the woodcuts feature bold and forlorn faces rendered in a deeply worked grain; and the etchings are epic, containing fully formed scenes (from home life to local watering holes) that unfold scratch by scratch.

Eisenman’s lithographs are the most introspective of her prints. To create them, she worked with Andrew Mockler of Jungle Press Editions in Brooklyn; they produced eleven prints together over a year and a half.1 All the works depict figures— alone, as couples, and even, in a few instances, in a trio. The scenes oscillate between feelings of loneliness and alienation, on the one hand—a man holding his own shadow, a woman daydreaming in bed—and the possibility of connection, on the other, via “sloppy barroom kisses” or a portentous game of Ouija. The prints also reflect Eisenman’s deep study of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European art, particularly Impressionism and German Expressionism. In preparation for the project, she and Mockler made several trips to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to view its print collection, studying Edvard Munch’s moody, willowy portraits; Odilon Redon’s oneiric figures; and Pablo Picasso’s Suite 347 (1968), among others.2 These artists, like Eisenman, were each attracted to the directness and immediacy of lithography, with its rapid mark-making and printing properties, as well as the generative ability to “open up” lithographic stones—adding revisions to the printing surface to create new images from existing ones.

One lithograph stands out from the rest, not only for its large scale but also for its overtly political message. Tea Party (2012) is both a commentary on and a portrait of the conservative political movement of the same name that emerged in early 2009 during President Barack Obama’s first term in office. In the print an eighteenth-century American revolutionary and a rotund businessman on the left face a skeleton on the right. Against a marbled and grainy blue and black background, they stand in a pool of water, holding onto a pole that is part scythe, part American flag, and crowned with a pineapple (the traditional symbol of hospitality in colonial America). The revolutionary sports an anus-shaped ear while the businessman’s ear is pinned shut, suggesting that both are impervious to outside influence or even reason. The message of the work is clear: the crossing of political evangelism with the consolidation of capital owned by “the top 1 percent” can only be met with a swift demise.3 Tea Party articulates Eisenman’s political orientation, as the artist reproduces not only this particular trio of figures across her work in various mediums but also the form of the print itself. “My reiteration of the image,” she says, “is a resistance that meets Tea Party members’ own. It is my insistent resistance.”4

While Eisenman’s prints on the whole are poignantly evocative, channeling a variety of recognizable human experiences, including love, sex, motherhood, and alienation, Tea Party strays from this sensibility. It has more in common with her politically inflected paintings of the late 2000s, which directly and indirectly addressed the current affairs of the day, including the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the so-called Great Recession, and the bailout of the automobile industry. These works vary widely, from portraits of Buster Keaton (who happens to share an uncanny likeness with the artist) as a pensive Hamlet and a deep-sea diver, to paintings of beer gardens where one can go, as Eisenman has commented, “to socialize, to commiserate about how the world is a fucked-up place and about our culture’s obsession with happiness.”5

Eisenman estimates that she has created at least five Tea Party paintings, prints, and drawings since 2011, in tandem with the movement’s swift ascent in contemporary American politics.6 The name of the group is taken from the Boston Tea Party of 1773, in which American revolutionaries protested British colonial policies by dumping more than forty tons of imported Chinese tea into Boston Harbor. The movement crystallized following President Obama’s announcement of the Homeowners Affordability and Stability Plan in February 2009. The bill was intended to reform the American housing market, which had plunged following irresponsible lending and wild speculation by the banking industry.7 At present the majority of the Tea Party is active as a conservative subgroup of the Republican Party, with roughly 10 percent of Americans identifying as members.8 Major figures include former governor of Alaska Sarah Palin, Texas senator Ted Cruz, former US representative Ron Paul, and political commentator Glenn Beck. Among the Tea Party’s “non-negotiable core beliefs” are the need for a strong military, more American jobs, protected gun ownership, reduced government size and involvement, tax cuts, and strict policies on illegal immigration.9

Eisenman is one among several contemporary artists who have explored the Tea Party’s constitutional conservatism and patriotic fervor in their work; others include Lauren Frances Adams, Paul Chan, Goshka Macuga, and Catherine Opie.10 In a major painting also titled Tea Party that followed later that year, four figures sit around a table in a bunker or closet. They settle in, prepared for impending doom: one snoozes, hugging a rifle, while her companion fiddles with sticks of dynamite. A raggedy Uncle Sam type in torn trousers slumps forward in his chair, a used tea bag dangling from his fingers. Behind them are stacked piles of gold bars (rendered in real gold leaf) alongside cans of tuna fish and a large jug of water. Depicted as isolationist and incapacitated, the movement, according to Eisenman, shares more in common with separatist militias than with politicians entrenched in Washington and as such, she suggests, is hardly equipped to deliver revolution.

Contemporary depictions of the Tea Party movement in the media stress its decentralized organization and collective power, evinced primarily through photographs of rallies and protests in which large groups of individuals band together, wave American flags, and brandish protest signs. Eisenman appropriates such popular portrayals in her Tea Party works, producing her own iconic image to exact political critique. Her lithograph, for example, elevates the large 2011 painting to the level of allegory. Stripping the painting of its specificity, she relies on spare formal and narrative devices to denounce American conservatism. She streamlines the movement into three figures constituting what she deems the “holy trinity” of revolutionary, businessman, and skeleton.6 In addition, the blatantly graphic style of the figures references the satirical aim of political cartoons (which, it bears mentioning, were regularly published as lithographs in the nineteenth century). This simplification of the movement's representation, along with such cues as the figures’ peculiar ears, suggests absurdity and impotence rather than the transformative momentum of a critical mass.

While Eisenman’s own political position is reflected through her choice of subject matter, the formal qualities of her Tea Party works are indicative of a larger politics of art-making central to her practice. She does not adhere to conventional methods of applying paint to canvas or a mark to a printing plate. Globs of paint accrete in certain areas as though she were scraping off excess from her palette knife. She enunciates a figure’s mouth simply by squeezing a tube of paint across the surface of the canvas to effect a tight-lipped smirk. Using painted insulation foam, she has even made several portraits—of a devil and a woman with “saggy titties”—that resemble bas-reliefs more than two-dimensional paintings. Many of her monotypes approximate finger-painting or elementary school collages in their freely associative application of both swirling ink and magazine clippings. Furthermore, Eisenman’s rendering of the body (and what it variably denotes) is rarely fully or clearly determined. While nude figures—almost all women—exuberantly flaunt their sex, clothed figures often appear ambiguously gendered. Sloppy Bar Room Kiss (2011), another image that Eisenman has developed as both a painting and a lithograph, features two individuals in a drunken embrace. Emphasis is placed, however, on the visual symmetry of the heads turned toward each other and the scene’s heightened amorous moment rather than the couple’s specific sexuality. This in-betweenness is a signature feature—and, one might argue, strength—of her work. As Julia Bryan-Wilson has written, “the oscillation between texture and atmospheric mood generates productive, queer friction . . . as the eye cannot rest only on the surface of the painting, but is also pulled into its emotional punch by way of representation.”12 In other words, Eisenman’s formal strategies not only are visually seductive, but even more significantly, they vibrate with deeper notions of bodily and sexual freedom— notions that stand largely in opposition to the kinds of binary, heteronormative values and unions espoused by right-wing groups such as the Tea Party.

The constructive tension between Eisenman's radically heterogeneous practice and her repeated conjuring of the Tea Party approximates an activist intention. The Dutch critic Sven Lütticken optimistically imagines art’s potential to create a space for reflection through repetition, whether, for example, in reenactments and remakes or by viewing copies of a limited, editioned work of video art. “Operating within contemporary performative spectacle, if from a marginal position,” he writes, “art can stage small but significant acts of difference.”13 Extending his argument, Eisenman’s multiple Tea Party works create a meaningful riposte to conservative ideology through their proliferation as both image and print. By animating her “holy trinity” into a serial image, she echoes its actual and continual enactment in today’s public sphere. Her Tea Party works function as visual filibusters, disrupting the barrage of images and polemical rhetoric that cloud our newspapers, television and computer screens, and mobile devices. In effect she has staged with her “insistent resistance” her own multimedia protest. Just as a lithographic stone can be opened up and reworked to produce anew, Eisenman has created an image that opens itself up to repeated deployment in public and in private, in galleries and homes, online and in real life. Repetition can make a difference.

- 1 I would like to thank Andrew Mockler for generously sharing details of Eisenman’s project with me, as well as for his illuminating insights on lithography in general

- 2 See Faye Hirsch, “Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prolifically,” Art in Print 2 (January–February 2013), artinprint.org/article/nicole-eisenmans-year-of-printing-prolifically/, for a helpful overview of Eisenman’s print- making project. Of particular relevance to her series is Picasso’s 347 Suite, comprising hundreds of prints the artist made over a mere six-month period, at the age of eighty-six. The series is notable not only for the vast number of works and Picasso’s sophisticated mastery of such etching techniques as drypoint, intaglio, and aquatint but also for the breadth of its subjects, featuring a large cast of characters (circus performers, musketeers, musicians, and so forth) that the artist developed over his career.

- 3 For more on the notion of “the 1 percent” see Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%,” Vanity Fair, April 30, 2011, www.vanityfair.com/news/2011/05/top-one-percent-201105.

- 4 Nicole Eisenman, conversation with the author, September 2015.

- 5 Nicole Eisenman, on her exhibition Coping at Galerie Barbara Weiss in Berlin, as told to Brian Sholis, Artforum.com, September 6, 2008, artforum.com/words/id=21064.

- 6 Eisenman, conversation with the author.

- 7 For more on this, see Ben McGrath, “The Movement: The Rise of Tea Party Activism,” New Yorker, February 1, 2010, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/02/01/the-movement.

- 8 See Karlyn Bowman and Jennifer Marisco, “The Tea Party at Five,” American Enterprise Institute (February 2014), www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/-the-tea-party-at-five-an-america....

- 9 For all fifteen of the party’s “non-negotiable core beliefs,” see www.teaparty.org/about-us.

- 10 Examples of this include Opie’s untitled 2010 photographs of Tea Party rallies, Macuga’s tapestry It Broke from Within (2011), Adams’s participatory installation We the People (2012), and Paul Chan’s essay “Progress as Regression,” e-flux journal 22 (January 2011), www.e-flux.com/journal/progress-as-regression.[fn] Eisenman’s first take on the subject, a small painting (Tea Party, 2011), was created in response to a prompt from the New York art critic Jerry Saltz on his Facebook page, asking artists why there had been no great art about the Tea Party.[fn] See “‘Nicole Eisenman / Matrix 248’: Tea Party Time,” SFGate, May 22, 2013, www.sfgate.com/art/article/Nicole-Eisenman-Matrix-248-Tea-Party-time-454....

- 11 Eisenman, conversation with the author.

- 12 Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Draw a Picture, Then Make It Bleed,” in Dear Nemesis: Nicole Eisenman 1993–2013 (St. Louis: Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis; Cologne: König, 2014), 99. Several art historians have begun to articulate the notion of a “queer formalism” in the work of Eisenman, Amy Sillman, Harmony Hammond, Scott Burton, and others. In addition to Bryan-Wilson’s essay, see “Queer Formalisms: Jennifer Doyle and David Getsy in Conversation,” Art Journal 72 (Winter 2013): 58–71, and William J. Simmons, “Notes on Queer Formalism,” Big, Red, and Shiny, December 16, 2013, bigredandshiny.org/2929/notes-on-queer-formalism.

- 13 Sven Lütticken, “An Arena in Which to Reenact,” in Life, Once More: Forms of Reenactment in Contemporary Art (Rotterdam, Netherlands: Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, 2005), 60.