Harriet Hosmer, Oenone, 1854–55

Erin Sutherland Minter

Formerly Curator of exhibitions for Special Collections, Washington University Libraries

Formerly PhD candidate in art history, Washington University in St. Louis

Oenone, Harriet Hosmer's first full-length, life-size sculpture, masterfully demonstrates the young artist’s technical acumen as well as her insightful engagement with the artistic discourse of American sculpture of the mid-nineteenth century. With a perceptive assessment of contemporary American viewers and potential patrons, Hosmer designed Oenone to balance classical decorum and pathos, erudition and accessibility, nudity and modesty. These dichotomies are inherent in the relationship between Neoclassical sculpture—with its traditional focus on idealized nude figures of heroic subjects—and American culture in the nineteenth century. While European, especially Italian, academic art demanded mastery of the nude figure, the relatively conservative American public had reservations about viewing nude sculpture, and a female artist evoking the nude was even more problematic.1 Oenone satisfies the academic viewer, accustomed to the undraped figures of ancient and modern European art, without offending a broader public with an unmitigated nude display. The traditionally reserved American audience had a growing interest in romantic, emotional literature and sculpture with a straightforward, sympathetic narrative. Hosmer creatively reconciled the refined, idealized classicism favored in academic art with the emotionally engaging qualities that appealed to broad audiences of popular exhibitions.

The modest amount of critical scholarship devoted to Hosmer since the early twentieth century, most of it written since the 1980s, has focused largely on her identity as a female sculptor and how gender informed her art.2 While this approach is valuable, I would like to consider Oenone in relation to its elucidation of Hosmer’s engagement with the cultural milieu of her time and her active positioning of herself within it as a professional sculptor of international acclaim.

In the 1780s Antonio Canova and his followers in Rome, especially Bertel Thorvaldsen, established the international style of Neoclassical sculpture.3 Inspired by the refined forms, idealized beauty, and harmonious figures of ancient sculpture, these artists developed the aesthetic principles favored by art academies in Europe and the United States throughout most of the nineteenth century. American Neoclassical sculpture remained devoted to beauty and idealized figures, but art and literature in the mid-nineteenth century increasingly appealed to a sense of pathos or romantic poignancy, engaging the audience’s sympathy. The unprecedented success of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852, for example, demonstrated the appeal of emotionally charged literature to a broad audience. Sculpture with heroic, tragic, and romantic subjects similarly captivated American viewers, both in the 1850s and throughout the nineteenth century. Commenting years later on Daniel Chester French’s Millmore Memorial (1889–93), Hosmer wrote, “Here the sculptor presents to us not only historic truth, but beauty of form and sentiment, pathos and outlines of harmony and grace.”4 In her own work Hosmer strove for this synthesis of beautiful forms, physical truth, and pathos.

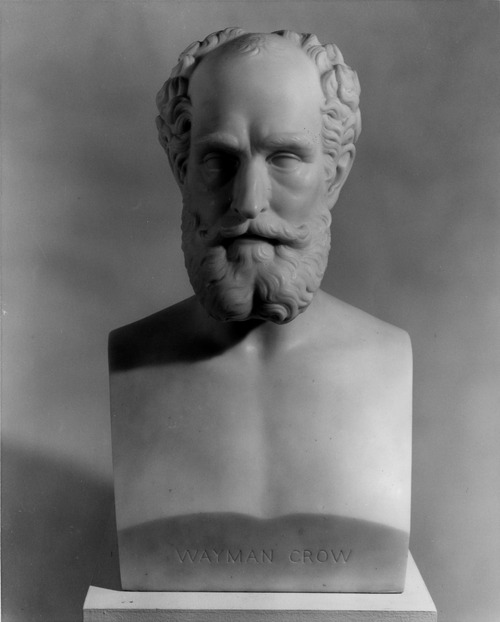

In 1852, determined to forge a professionally successful artistic identity, Hosmer went to Rome, where she studied with John Gibson, one of Canova’s pupils.5 Two years later Hosmer created Oenone as a commission by her American benefactor Wayman Crow. The sculpture also served as her artistic debut in the United States. Assessing the artistic and cultural environment of her intended American audience, Hosmer chose to represent the nymph whom Paris loved but abandoned to pursue Helen of Troy. Relegated to a brief mention in Ovid’s account of the Trojan War, Oenone was revived as a tragic, suffering victim in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s eponymous poem first published in 1832.6 The love-struck Oenone prophesied that Paris would be injured and offered to heal him if he returned. Shot by an arrow, the ill-fated soldier returned to his scorned love, who, indignant and heartbroken, refused to heal him, thus assuring his death. Overcome with despair afterward, she took her own life. Hosmer’s depiction of the nymph compels viewers to wonder whether Oenone awaits her lover’s return or remorsefully contemplates suicide. Although the Greek maiden’s perspective on the Trojan War was nearly unheard of in art prior to Tennyson’s poem, Hosmer’s most learned contemporaries were familiar enough with the subject that in a letter to Crow in 1856, the artist simply wrote “the figure represents Oenone abandoned by Paris.”7 While the mythological and literary associations of the figure appealed to erudite audiences, even the most casual viewer could engage with the sculpture’s palpable sense of sorrowful reflection.

To demonstrate her training among the Neoclassical masters of Rome, Hosmer used a fine-quality block of creamy white marble and worked the surface up to a high polish. Oenone’s features— including a strong nose, small mouth, and smooth features reminiscent of a Roman deity—masterfully emulate classical models. Her hair is parted in the middle and pulled back gently, allowing soft waves to frame her face. With the dignity of an allegorical bust sculpture, her idealized features betray little emotion. Rather, the sculpture’s mournful pathos is expressed through the body. Her lowered head and downcast gaze suggest an inward focus. The long, sinuous curve of Oenone’s back draws the eye downward, as her left foot slips off the circular base. Her left arm listlessly drops over her right leg; in contrast, she supports herself with her strong right arm. Gazing on the shepherd’s crook that Paris left behind, she seems lost in reflection. Her right hand and a bit of drapery spill over the edge of the sculpture base. This breach into the viewer’s space makes the sculpture more immediate, heightening the pathos without compromising the work’s classical appeal.

Throughout her career Hosmer maintained her devotion to classical aesthetics, asserting, “Lovers of all that is beautiful and true in nature will seek their inspirations from the profounder and serener depths of classic art.”8 Steeped in the masterpieces of Rome’s museums, Hosmer would have known the emotive power of the Dying Gaul, an ancient Roman copy of a Hellenistic sculpture of a fallen warrior wounded on the battle field. One of the most praised antiquities in Rome when Hosmer was there, the Dying Gaul has the firmly downcast gaze, supporting right arm, and resolute expression that reappear in Hosmer’s Oenone. The warrior’s pained yet controlled posture as he sinks to the ground also serves as a model for the classicized emotion that characterizes Oenone. In an age when art schools and museums in the United States displayed casts of famous antiquities, viewers would have recognized this artful allusion to the venerated past, as well as to Lord Byron’s dramatization of the ancient mythological figure in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1818), in which the poet described the Dying Gaul as one who “consents to death, but conquers agony.”9

The most commercially successful sculpture in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century was Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave, which arrived in New York in 1847. Several copies of the sculpture toured commercial galleries in the late 1840s and 1850s, attracting unprecedented audiences. The nude sculpture depicted an adolescent girl “cloaked in modesty,” who was promoted as the victim of Turkish captors.10 Bound by chains, she stands tall, her head held high, her face blank and expressionless.11 While the nudity of Powers’s statue caused some backlash, the controversy seemed to enhance the sculpture’s notoriety. Hosmer’s decision to represent Oenone half-nude suggests an engagement with the contemporary art scene, yet she was simultaneously careful to maintain a sense of modesty. While the Greek Slave presents a fully nude female for visual consumption by the audience, Hosmer’s partially draped Oenone seems to turn inward, to deflect the viewer’s gaze.

Moreover, Hosmer preserved the dignified expression of the Greek Slave while suggesting mournful reflection rather than a dispassionate, uncomprehending stare. Although Powers’s Greek Slave seems detached, pamphlets accompanying the work told a teary-eyed tale of a virtuous Christian maiden sold at a Turkish auction.12 Audiences, won over by the contrived narrative, waxed poetic about “her virgin soul” being “debased, defiled and trampled in the dust.”13 Arguably, Hosmer’s Oenone does not require a sentimental tale to evoke an emotional response. The art critic James Jackson Jarves wrote of Hosmer: “Her style is a decided rebuke to inane sentimentalists of the Powers class, which is a weak echo of the third-rate classical manner after it had abandoned beauty for prettiness. Miss Hosmer’s manner is thoroughly realistic.”14

While deftly infusing classically inspired sculpture with romantic pathos, Oenone offers viewers a glimpse of the predominant cultural and artistic trends that engaged a broad American audience in the mid-nineteenth century. Viewers steeped in Ovidian tales and Tennyson’s poetry could appreciate the sculpture’s narrative associations; at the same time, any viewer could appreciate the figure’s emotive expression. With this sculpture, Hosmer achieved a concordant synthesis of a classicizing mode and romantic pathos, popular appeal and erudition, nudity and propriety, while remaining firmly grounded in the traditions of ancient sculpture.

Harriet Hosmer’s purposeful integration of aesthetic elements demonstrates a determination that led to professional success. To this end, she managed to cultivate American patrons even while she lived in Rome. In a letter to Crow, Hosmer suggested, “If you hear of anybody who wants an equestrian statue ninety feet high, or a monument in memory of some dozen departed heroes, please remember that nun-like I am ready for orders. However, to be moderate and earnest, I mean that if anybody wants any small decent-sized thing I should be glad to furnish it.”15 The young sculptor’s quixotic jest betrays her boundless ambition and gently reminds her patron that, no longer a student, she was ready to support herself as a professional artist. Sending Oenone to St. Louis, in fact, proved to be instrumental to her success. Within a few years, she had sold numerous copies of her playful sculpture Puck (1855) and won significant commissions, including one for Beatrice Cenci (1856) at the Mercantile Library of St. Louis, thus launching her career as an ambitious and pragmatic professional artist.

- 1 See Laura R. Prieto, At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001), 86.

- 2 The artist’s biography is best known through Harriet Hosmer: Letters and Memories, ed. Cornelia Carr (New York: Moffat, Yard & Co., 1912), and Dolly Sherwood, Harriet Hosmer: American Sculptor, 1830-1908 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1991). For feminist approaches to her work, see especially Nicolai Cikovsky, Nineteenth-Century American Women Neoclassical Sculptors, Vassar College Art Gallery, April 4 through April 30, 1972 (Poughkeepsie: Merchants Press, 1972); Alicia Faxon, “Images of Women in the Sculpture of Harriet Hosmer,” Woman's Art Journal 2, no. 1 (1981): 25-29.; Joy S. Kasson, Marble Queens and Captives: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990); Joseph Leach, “Harriet Hosmer: Feminist in Bronze and Marble,” Feminist Art Journal 5, no. 2 (Summer 1976): 9-13, 44-45; and Vivien Green Fryd, “The ‘Ghosting’ of Incest and Female Relations in Harriet Hosmer’s Beatrice Cenci,” Art Bulletin 88, no. 2 (2006): 292-309.

- 3 Developing on the heels of the Enlightenment, Neoclassical art favored clarity, naturalism, and the idealized representations of the human body associated with Periclean Greek sculpture. Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s publications The Reflections on the Imitation of the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks (1765) and History of Ancient Art (1764) built on recent excavations of antiquities in Herculaneum and Pompeii, introducing artists and the public to the forms and subjects of ancient art. Antonio Canova developed a sculptural style of Neoclassicism that reveled in the beauty of pure white marble and idealized nude figures. Horatio Greenough was the first American sculptor to study the style in Rome, traveling to Italy in 1825. American artists continued to work in Italy to study from antiquity and have access to white marble and skilled carvers. Neoclassical sculpture in America focused on biblical, literary, classical, and moralizing themes. The style dropped off in popularity in the late 1870s. See William H. Gerdts, American Neo-Classic Sculpture: The Marble Resurrection (New York: Viking Press, 1973).

- 4 Carr, Harriet Hosmer, 332.

- 5 Although Hosmer traveled widely, she maintained a successful atelier in Rome for most of her career.

- 6 In a letter from the early 1850s Hosmer described herself and a friend “going frantic together over Tennyson and Browning.” Quoted in Sherwood, Harriet Hosmer, 35.

- 7 Hosmer to Wayman Crow, September, 1856, in Sherwood, Harriet Hosmer, 72.

- 8 Hosmer to an acquaintance, January 19, 1894, in Harriet Hosmer, 334.

- 9 Lord Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1818), canto IV, st. 140.

- 10 Reverend Orville Dewey was one of many writers who suggested the slave’s nudity was excused by her virtuosity. See Kasson, Marble Queens and Captives, 58.

- 11 Through the 1860s Powers produced dozens of replicas from his original conception of 1843, ranging from six full-length statues to numerous smaller-scaled and bust-length marbles. Joy Kasson remarked that “In the middle years of the nineteenth century, no American artwork was better known.” Ibid.

- 12 The pamphlets Powers had published to accompany his Greek Slave had the dual function of justifying the girl’s nudity and casting her as the tragic heroine of a heartbreaking tale.

- 13 As quoted in Kasson, Marble Queens and Captives, 65.

- 14 James Jackson Jarves, Art Thoughts (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1870), 308.

- 15 Hosmer to Crow, January 9, 1854, as cited in Sherwood, Harriet Hosmer, 102.