Connecting Literature and Visual Art

.png)

Introduction

This guide explores connections between literature and visual art through the permanent collection of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum. In this guide you will move chronologically from the nineteenth century to today, encountering artworks in a range of mediums by artists who were inspired by literature, whose works inspired the writing of literature, who were both visual artists and writers, and who incorporated text directly into their artwork.

Responding to Literatures Past and Present

"Lovers of all that is beautiful and true in nature will seek their inspirations from the profounder and serener depths of classic art." — Harriet Hosmer

Spend a moment looking at this sculpture by American artist Harriet Hosmer (1830–1908). Consider the figure’s body language: What moods or emotions come to mind as you look at this artwork?

Hosmer looked to ancient Greek mythology while also responding to Victorian-era literary taste for this sculpture titled Oenone, begun in 1854 and completed in 1855 at the artist’s studio in Rome.

In 1851, after being barred from anatomy classes near her home in Massachusetts, Hosmer became the first woman to study anatomy at what later became Washington University’s School of Medicine. During this time Hosmer lived with the family of Wayman Crow, one of the founders of the university, who became an important patron and supporter of Hosmer’s work. This sculpture, which she made for Crow, was the first full-figure, life-size work that Hosmer created after moving to Rome in 1852 to study Neoclassical sculpture. Crow gifted the work to the Washington University art collection, and it served as Hosmer’s artistic debut in the United States.

Oenone depicts the nymph of Greek mythology who was the lover of Paris before he abandoned her to pursue Helen of Sparta, igniting the Trojan War. Prior to these tragic events, Oenone prophesied that Paris would be injured in Sparta and begged him not to go. When Paris refused to heed her warning, Oenone told him he should return to her on Mount Ida if he was wounded, for only she could heal him. During the ensuing war Paris was struck by an arrow and returned to Mount Ida seeking Oenone’s aid; she refused to heal him, however, because he had betrayed her for Helen. Not long after sending him away, Oenone regretted her decision and rushed after the wounded Paris. She was too late and found that he had already died. Overcome by grief, Oenone flung herself onto Paris’s flaming funeral pyre.

Hosmer’s interpretation of Oenone shows her seated on the ground, head bent to gaze down at Paris’s shepherd’s crook. Oenone’s idealized facial features echo classical models and betray little emotion, yet the sculpture’s mournful pathos is expressed through the sloping curves of the body. Oenone appears lost in reflection, her index finger coming close to but not touching the shepherd’s crook, a stand-in for her absent lover.

Hosmer’s depiction of Oenone alludes to the framing of this moment within a narrative, yet it does not tell us in what part of the story we find her―does she still await Paris’s return from Sparta, or is she regretting and reconsidering her decision to withhold from him a cure?

Oenone is only briefly mentioned in Greek and Roman accounts of the Trojan War, making her an obscure choice of subject matter if it were not for the recent revival of interest in her tragic tale through the poetry of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Tennyson penned an eponymous poem in Oenone’s voice in 1829 while traveling through the Pyrenees to aid a group of rebels in northern Spain. By the time Hosmer began this work, Tennyson was poet laureate to Queen Victoria and a bona fide literary celebrity whose works were widely read. Hosmer makes a layered literary reference with this sculpture—to ancient Greek mythology and Roman literature befitting her Neoclassical training, but by way of the Victorian celebrity poet who had brought new attention to Oenone as a sympathetic heroine. Hosmer’s choice of subject matter balances the classical with the contemporary, as she responds to literary traditions both past and present to carve a name for herself.

Read Tennyson's dramatic monologue “Oenone.”

Up next: Harriet Hosmer was inspired by classical mythology and contemporary poetry for the subject of her sculpture Oenone. We now turn to a work by Edouard Manet that caused controversy over the provocative poem it inspired.

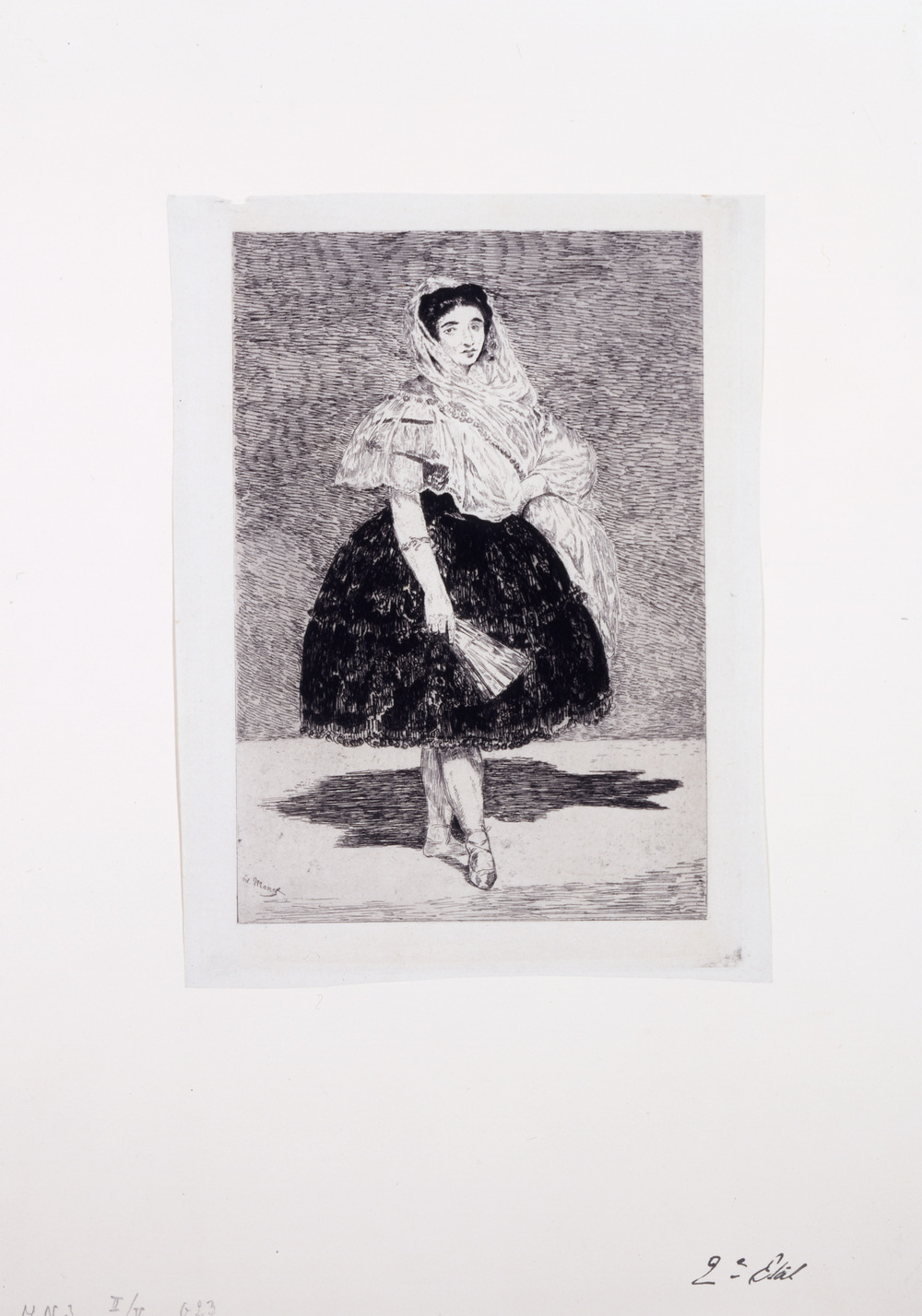

A Painting That Inspired Poetry

When the Royal Ballet of Madrid came to Paris in 1862, Edouard Manet did not hesitate to paint a portrait of Lola de Valence, a dancer famous for her beauty. The work—and this etching made after it—is an example of “espagnolisme,” a taste for all things Spanish in nineteenth-century French visual culture that was fueled in part by France’s brief occupation of the Spanish throne during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). Manet would continue his interest in Spanish culture by traveling to Spain in 1865 to study artists like Francisco Goya and Diego Velázquez.

A modernist painter, Manet’s choice of subject reflects the rise of a culture of public spectacle possible through new technologies and entertainment spaces such as the café-concert and opera. Rather than foreground the act of looking, the portrait highlights the persona of a celebrated performer. The sparse background focuses our attention on her dynamic pose as well as her costume, which includes a lavish mantilla (a traditional Spanish lace or silk scarf), ballet slippers, and a fan that she holds in her right hand.

When Manet’s friend the poet Charles Baudelaire saw Lola de Valence, he celebrated the dancer’s beauty in what was considered an erotic quatrain, published in his controversial collection, Les fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil):

Lola de Valence

Entre tant de beautés que partout on peut voir,

Je contemple bien, amis, que le désir balance;

Mais on voit scintiller en Lola de Valence

Le charme inattendu d’un bijou rose et noir.

Lola of Valencia

Among such beauties as one can see everywhere

I understand, my friends, that desire hesitates;

But one sees sparkling in Lola of Valencia

The unexpected charm of a black and rose jewel.

— Charles Baudelaire, The Flowers of Evil/Les fleurs du mal, trans. William Aggeler (Fresno, CA: Academy Library Guild, 1954)

Baudelaire wished for his poetic response to be displayed on the painting’s frame, directly linking word and image and visually framing the viewer’s interpretation of the portrait. In the end, when Lola de Valence was first exhibited at Galerie Martinet in 1863, the quatrain was displayed on a plaque next to the painting.

Produced in the same year as Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass) (1862–63) , one of three paintings by Manet that was rejected by the state-sponsored Salon of 1863 for its shocking content, Lola de Valence also stirred public controversy; this was due in large part, however, to the content of Baudelaire’s poem. In his 1867 review of the painting, writer and critic Emile Zola is careful to note that while he does not defend the lines of the poem, they do perfectly capture Manet’s application of paint and the bold opposition of colors that produce an “unexpected charm.”

Do you agree with Zola that Baudelaire’s quatrain changes how we view Manet’s representation of Lola de Valence?

Up next: Manet’s painted and Baudelaire’s written images of Lola de Valence became inextricably tied together. We will next look at a work by the artist Ludwig Meidner, who was both a painter and a writer.

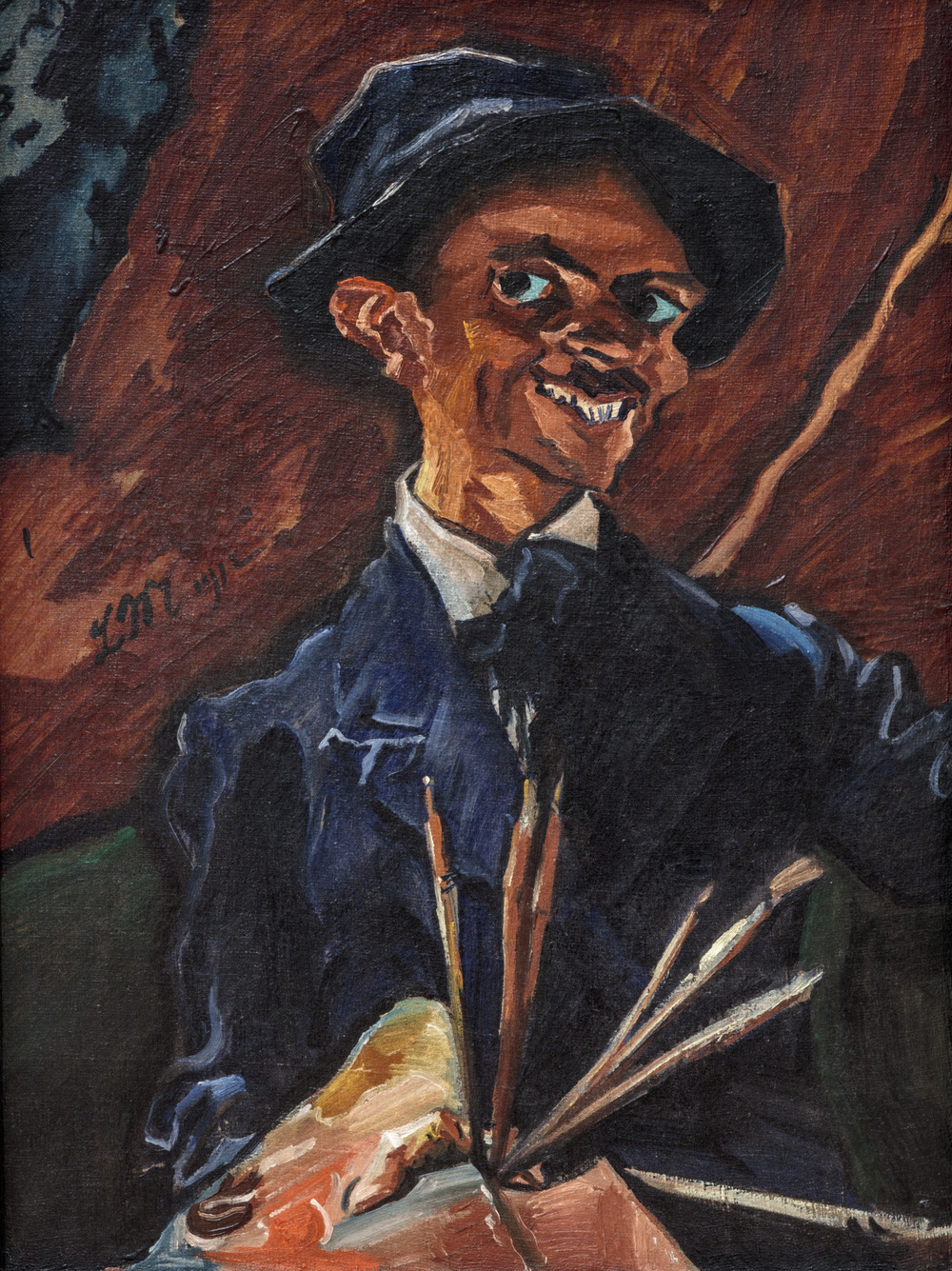

Self-Portraits in Paint and Words

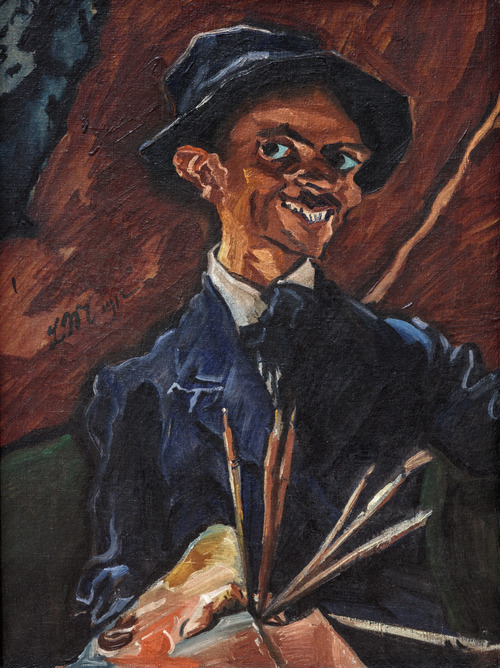

What stands out to you about this painting? What do you notice about the colors and brushwork?

In the tumultuous environment of pre-World War I Berlin, German artist Ludwig Meidner chose to turn inward, exploring the interplay between his emotional state and his surroundings in an extensive series of self-portraits, to which this example belongs. Art historian Victor Miesel, author of Voices of German Expressionism, described Meidner as “one of the most anxiety-ridden and high-strung of all the Expressionists;” his sideways glance, mischievous smile, dark color palette, and agitated brushstrokes infuse this 1912 self-portrait with a sense of emotional unrest that can also be seen in his apocalyptic urban landscapes that speak to the chaos leading up to World War I and his interest in biblical prophets’ visions of destruction. Meidner often referred to the city as a “battlefield,” inviting connections between the modern landscape of Berlin and the upcoming war.

In 1916 Meidner was drafted into the German army and served as a French-language translator in a prisoner-of-war camp. Without access to paints, he turned to drawing and writing, penning prose works including Septemberschrei: Hymnem, Gebete, Lästerungen (September Scream: Hymns, Prayers, Blasphemies; 1920). In this volume containing fourteen lithographs Meidner reflected on the period in 1912 when he made this self-portrait:

“I shall never be able to forget that summer. Befouled over and over again by scabies, misery, and madness it made me old, the plans of my youth were blasted and my courage crumbled. Arrayed in a smock so plastered with dried paint that it was stiff like armor, girded with a ravenous palette and brushes bared like teeth, so stood I steadfast the whole night through and painted myself in the leering mirror. . . .Within me crackled far-off spaces and the trumpet blasts of catastrophes yet to come. . . . Oh savage bloated bell, jagged arms and legs, oh face split with diabolical laughter—and then the laughter turned rancid.”

How do the descriptions in this text compare to Meidner’s painted self-portrait?

On the back of this canvas is an earlier composition that Meidner painted of his bedroom around 1909. Meidner frequently painted on both sides of his canvases, and it is likely that he would not have considered this interior scene, which does not include his signature, to be a finished work. The cramped space and simple furniture suggest the humble existence of the then impoverished artist. The painting was recently conserved and reframed so that both sides are visible.

Up next: While Meidner looked inward to probe the world of emotions through expressionistic painting and prose, Jacques Mahé de la Villeglé mined his art from city streets.

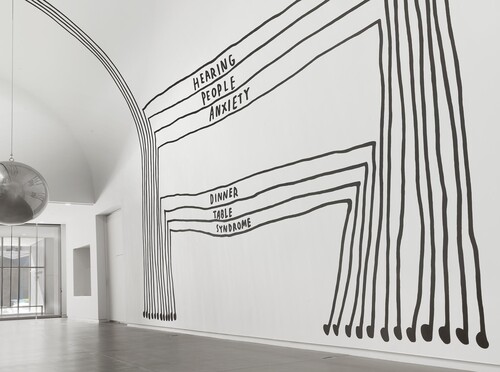

Found Poetry

In the late 1940s the French artist Jacques Villeglé first introduced décollage, an artistic practice that entailed collecting torn poster fragments from public spaces as readymade artworks. Rue du Temple—manuscrite is named for the street in Paris where Villeglé found the scraps that comprise the work. Using the remnants of defaced propaganda posters, he presents a palimpsest of textual fragments that show the political rhetoric in the tide of leftist protests that swept through Paris in 1968 and abstractly evoke France’s national tricolor flag.

What words or phrases can you make out?

Villeglé was a member of the Nouveaux Réalistes, a group of artists interested in everyday materials from the urban environment. His work can be viewed as “found poetry” whose meaning is derived from the random juxtapositions of words and phrases. Villeglé described the rips and tears of the posters as made by an “anonymous lacerator,” a person or natural force like the weather that created this layered and ripped form. This mode of abstraction challenged the artist’s heroic subjectivity conveyed through mark-making that is often associated with postwar Abstract Expressionism. Instead, the artist's only role is to encounter the work of art as it exists on the city streets, to tear it off the wall, and to mount it on a canvas. In this way Villeglé collaborates with the public spaces and the people of Paris to make the work. The technique serves to archive the contested sociopolitical visions of a particular time and place.

What might a found poem from a street in your community say about the time and place in which you live?

Up next: Villeglé brought text directly onto the canvas without altering the state in which he found the torn and layered posters. We will now explore textual works by Glenn Ligon, whose practice involves physically manipulating passages from literary works.

The Art of Quotation

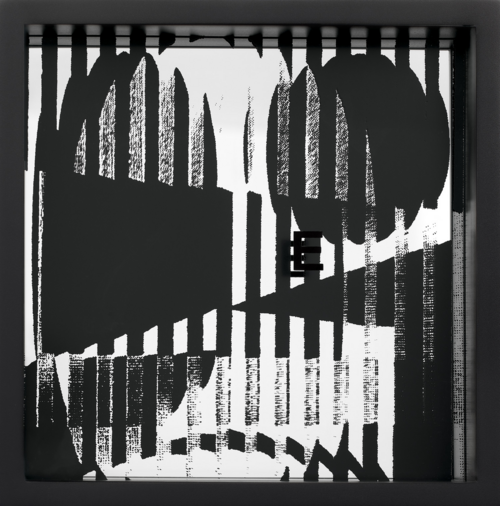

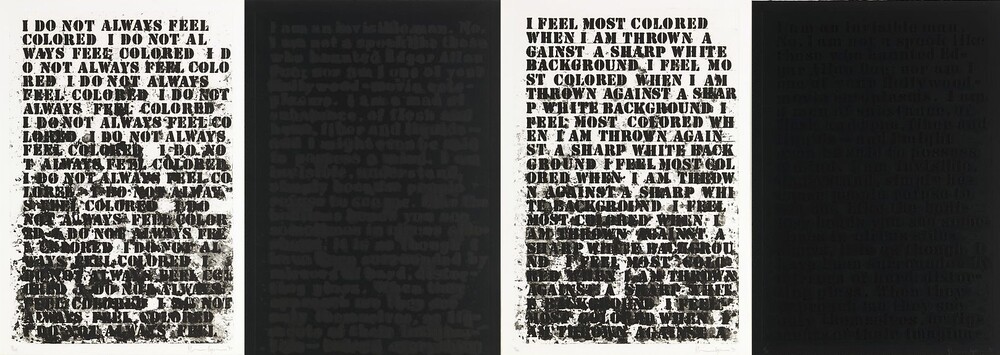

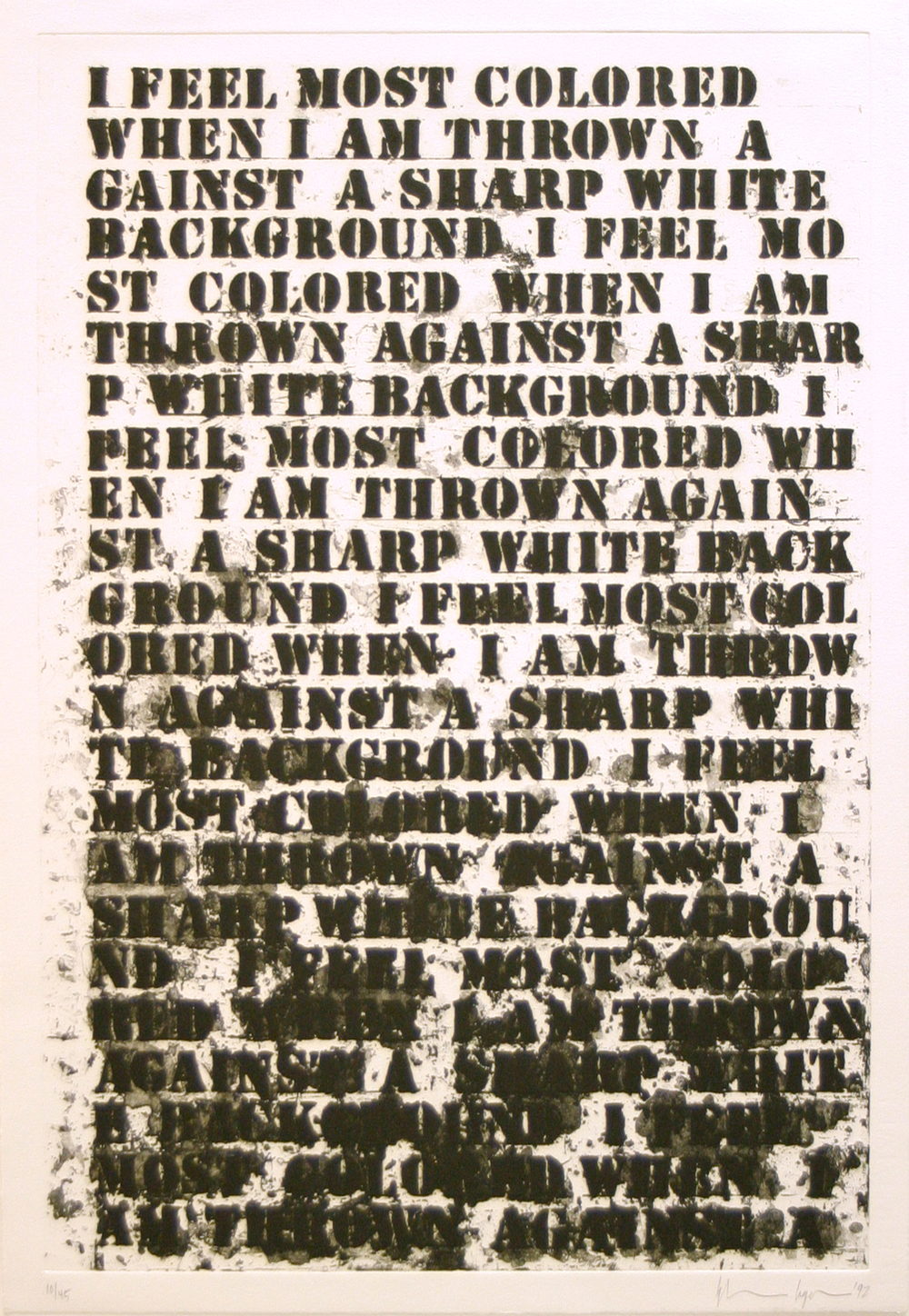

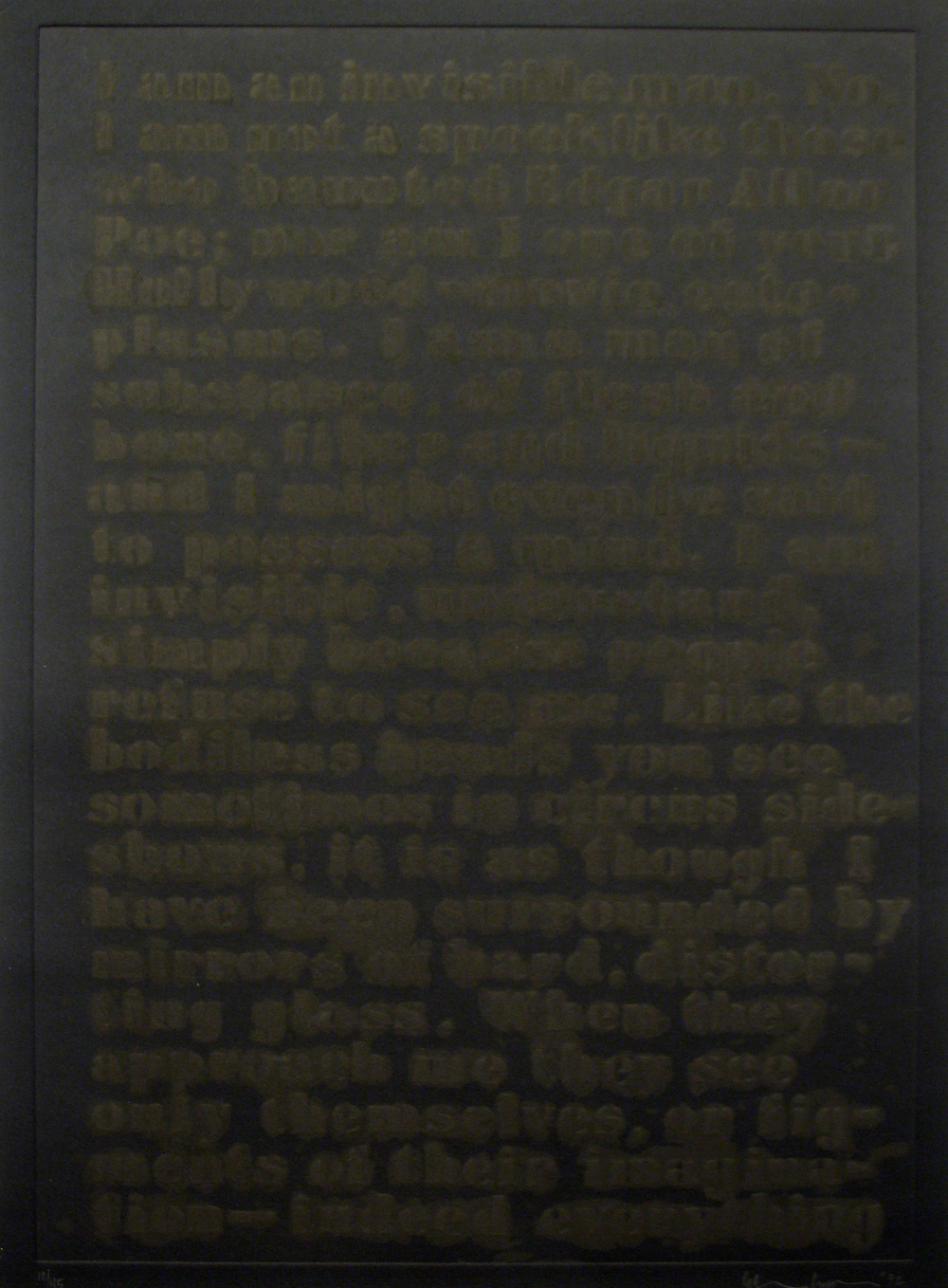

Concern with issues of legibility, language, and American history are central to Glenn Ligon’s artistic practice exploring identity and representation. Early in his career Ligon began directly incorporating the things he was thinking about and reading into his work through textual quotation. The four prints included in Untitled (Two White/Two Black) demonstrate Ligon’s engagement with literary sources and his exploration of the efficacy of language and visual images as modes of communication.

“There’s nothing wrong with self-expression, it just has its limits, and I think that the things that I was interested in were already in the world, and so they didn’t need me to create them again in that way, they just needed for me to have them be brought into the work. The work became more about quotation, using text from various literary sources. I read whatever I feel like reading, and if something stays in my head long enough it might turn into art.” — Glenn Ligon

The two prints with white backgrounds in Untitled (Two White/Two Black) repeat the lines “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background” and “I do not always feel colored.” These quotations are from Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston's 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” in which she describes her shifting awareness of her racial identity in different situations. Taken out of the context of Hurston's autobiographical essay, the first-person voice might ask us to consider who is speaking.

The two prints with black backgrounds present the opening lines of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man. The text explores the social invisibility experienced by its narrator, a black man who describes himself as “invisible. . .simply because people refuse to see me.” Ligon’s application of black letters on a black background make them difficult to decipher, both animating and obscuring the text as the viewer attempts to read.

Ligon invites us to explore the relationship between literary texts across different historical moments. In all four prints the stenciled letters on black and white backgrounds start out crisp but become increasingly blurred, visualizing the erasure and othering of people of color within white supremacist society.

How do the presentation of text, the choice of colors, repetition, and increasing illegibility contribute to the meaning you find in this work?

Ligon has said that in his art-making practice he is engaged in a “project of trying to describe what America means.” What can these passages by Hurston and Ellison tell us about America? What texts might you turn to in trying to describe what America means?

Hear Glenn Ligon speak about his personal history and the disparate influences that contribute to his work in this Art21 video.

Up next: The next work is made by Tim Rollins + K.O.S., an artist collaborative who used well-known works of literature as springboards for representing their own identities and experiences.

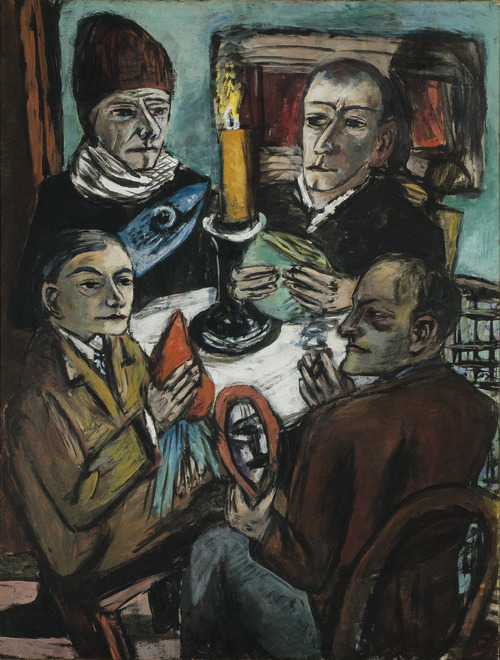

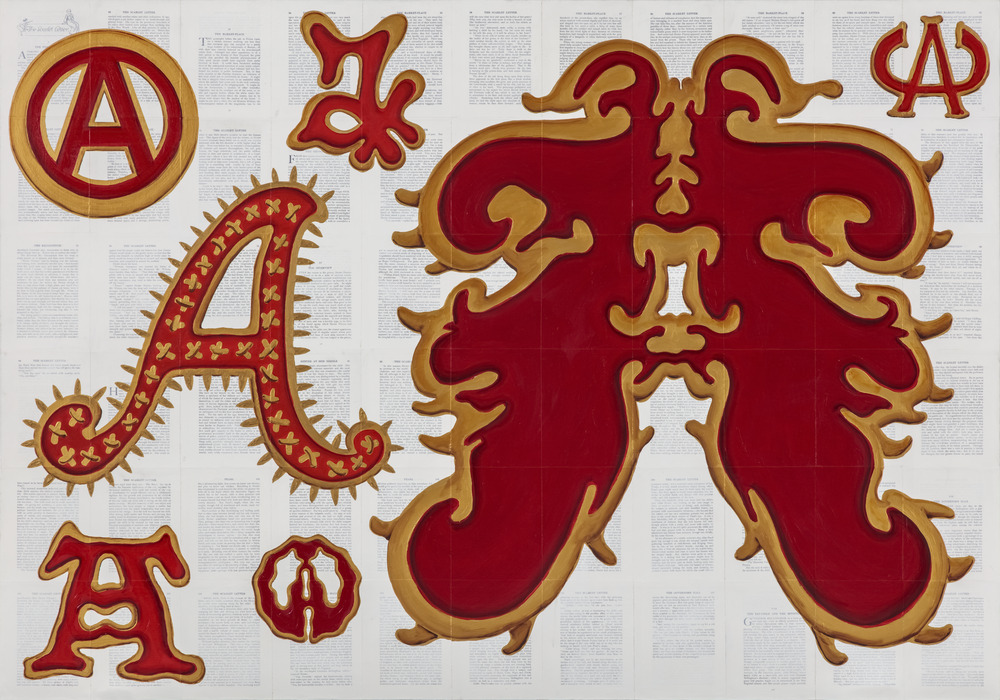

Telling One's Own Story

In 1981 Tim Rollins developed curriculum for Intermediate School 52 in the South Bronx that incorporated art-making with reading and writing for students classified as academically and emotionally “at risk.” Rollins and his group of young artists known as K.O.S. (Kids of Survival) followed a collaborative process of “educating by art making.” In a process they call “jammin’,” Rollins or one of the students read aloud from a selected text while the other members drew, relating the stories to their own experiences. Rather than reading books as received knowledge, Rollins and K.O.S. painted directly on texts, creating works that visualized their learning experience.

For this work they first distilled a symbol—a red letter A—from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1850 novel The Scarlet Letter. Next, each student developed their own version of this symbol. Finally, these were worked into a collective statement. Hawthorne’s novel traces the struggles of Hester Prynne, a woman convicted of adultery in seventeenth-century Puritan Boston. As punishment for her crime, Hester was forced to wear a red A on her chest. Despite her critics’ intentions, Hester wears the letter with pride, turning a symbol of derision into one of empowerment. Rollins and K.O.S.’s large, mutated A’s painted atop a grid of book pages also refer to the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, the prevention of which was often met with puritanical attitudes.

The collaboration between Rollins and his students eventually moved out of the classroom and became an after-school program called the Art and Knowledge Workshop. In 1986, Rollins and K.O.S. had their first exhibition at Jay Gorney Modern Art. By exhibiting in galleries and museums, the collaborative insisted that their work be understood as fine art. In 1994, Rollins and K.O.S. moved into a studio in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, and from this home base they expanded their project to bring workshops into schools and arts institutions nationally and internationally.

“To dare to make history when you are young, when you are a minority, when you are working, or nonworking class, when you are voiceless in society, takes courage. Where we came from, just surviving is ‘making history.’ So many others, in the same situations, have not survived, physically, psychologically, spiritually, or socially. We were making our own history. We weren’t going to accept history as something given to us.” — Tim Rollins

How does Rollins’ statement about “making history” with K.O.S. speak to their art-making practice and its relationship to literature?

What do you think of the inclusion of the phrase “The Prison Door” in the title of this artwork?

Up next: We will conclude our tour looking at works by Shirin Neshat that bring together poetry and portraiture, calligraphy and photography, to draw connections across time and place.

Surface Inscriptions

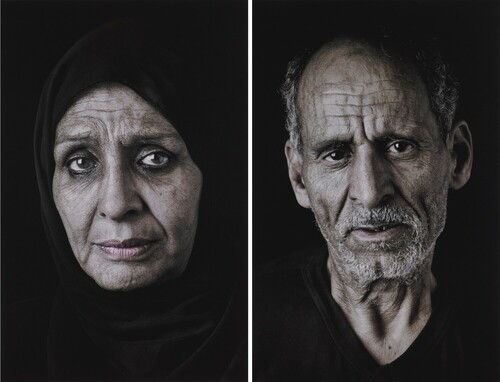

The two portraits Sayed and Ghada are from the 2013 series Our House Is on Fire made by US-based Iranian artist Shirin Neshat in Cairo following the Arab Spring. Neshat traveled to Egypt to speak with and photograph people who had lost family members during the 2011 revolution. She chose specifically to photograph older people because of their extensive experiences of changing political landscapes. Neshat invited sitters to share their stories and to have their portraits taken, using their body language and facial expression to communicate their experience to the viewer.

While not visible at first, close inspection reveals the many lines of minuscule calligraphy carefully written across the photographed faces. Rather than telling the stories of the people she interviewed, Neshat chose to inscribe poems in Farsi, including several by poets of the Iranian Revolution, and poems translated into Farsi from Arabic. The tiny lines of script blend into the texture of the sitters’ faces and merge with the lines of their skin. The series’ title is a line from the poem “A Cry” by the Iranian revolutionary poet Mehdi Akhavan Sales (1928–1990). Through her choice of texts, Neshat draws a connection between the 2011 revolution in Egypt and the Iranian Revolution of the 1970s, as well as between the experiences of her sitters and her own experiences of loss and grief as an exiled artist.

“A Cry” by Mehdi Akhavan Sales

How does the bringing together of different voices and histories through poetry and portraiture influence our empathetic response?

Why might Neshat have chosen to obscure the texts in this way?

In this video from the Rauschenberg Foundation, Shirin Neshat explains her process and reflects on the experience of making Our House is on Fire:

Notes

Childs, Elizabeth C. Spectacle and Leisure in Paris: Degas to Mucha. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2017.

“Glenn Ligon in ‘History.’” Art in the Twenty-First Century. Season 6, episode 3. Aired April 28, 2012, on PBS. https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s6/glenn-ligon-in-history-segment/

Ketner, Joseph D., et al. A Gallery of Modern Art at Washington University in St. Louis. St. Louis: Washington University Gallery of Art, 1994.

Miesel, Victor H. Voices of German Expressionism. London: Tate Publishing, 2003.

Minter, Erin Sutherland. “Harriet Hosmer.” In Spotlights: Collected by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, edited by Sabine Eckmann. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2016. https://www.kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/learn/learning-resources/hosmer-harriet-oenone-185455/type/essays

Popiel, Anne “Ludwig Meidner.” In Spotlights: Collected by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, edited by Sabine Eckmann. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2016. https://www.kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/learn/learning-resources/meidner-ludwig-selbstbildnis-self-portrait-1912/type/essays

Rashidi, Yasmine El. “Egypt: Face to Face.” The New York Review of Books, March 18, 2014. https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2014/03/18/neshat-egypt-face-to-face/

Zola, Emile. “Une nouvelle manière en peinture: Edouard Manet.” Revue du XIXe siècle, January 1, 1867.

Harriet Hosmer (American, 1830–1908), Oenone, 1854–55. Marble, 33 3/8 x 34 3/4 x 26 3/4". Gift of Wayman Crow Sr., 1855.

Edouard Manet (French, 1832–1883), Lola de Valence, 1862–63. Etching and aquatint on chine volant, 10 5/8 x 8". University purchase, Parsons Fund, and with funds from Mr. and Mrs. John Peters MacCarthy, 2002.

Ludwig Meidner (German, 1884–1966), Selbstbildnis (Self Portrait), 1912 [recto] / Untitled, c. 1909 [verso]. Oil on canvas, 31 3/4 x 23 11/16". Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Sydney M. Shoenberg Jr., 1963.

Jacques Mahé de la Villeglé (French, b. 1926), Rue du Temple—manuscrite, 1968. Torn posters mounted on canvas, 45 5/8 x 31 13/16". University purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Robert Shoenberg Fund, 2011.

Glenn Ligon (American, b. 1960), Untitled (Two White/Two Black), 1992. Portfolio of 4 prints: softground etching, aquatint, spit bite, and sugar lift, 25 1/8 x 17 1/2" each. University purchase, Charles H. Yalem Art Fund, 1997.

Tim Rollins (American, 1955–2017) and Kids of Survival (K.O.S.), The Scarlet Letter—The Prison Door (after Nathaniel Hawthorne), 1992–93. Acrylic and book pages on linen, 54 1/8 x 77 3/16 x 1 3/4". University purchase, Bixby Fund, 1993.

Shirin Neshat (Iranian, b. 1957), Sayed and Ghada, from the series Our House is on Fire, 2013. Digital pigment prints, 23 15/16 x 15 9/16" each. Gifts of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, 2016.

All artworks are copyright the artist or the artist’s estate unless otherwise specified. Images on this tour are for educational purposes only and are not licensed for commercial applications of any kind.

We are committed to encounters with art that inspire creative engagement, social and intellectual inquiry, and meaningful connections across disciplines, cultures, and histories. Do you have ideas or suggestions for other learning resources? Is there an artist or topic that you would like to learn more about? We would love to hear your feedback. Please direct comments or questions to Meredith Lehman, head of museum education, at lehman.meredith@wustl.edu.